The Incredible Surge of Groundwater Extraction in California

In California, groundwater extraction for agriculture has boomed over the past 75 years, and the average well drilled today has more than doubled in depth compared to wells drilled in 1940, according to Department of Water Resources data.

If the animation above doesn’t load, or appears slow, try viewing it here.

California’s demand for water exceeds naturally available supply, so it pumps water out of the ground

California agriculture is at an all time peak, grossing around $50 billion in farm and ranch output in 2018 1. The agricultural giant is responsible for 33% of the vegetables and 66% of the fruits and nuts consumed in the USA 1. California supplies 80% of the world’s almonds, and 34-40 percent of the world’s walnuts and pistachios 2. But California is also a dry land that suffers from drought and wildfire. There simply isn’t enough water in any given year to support all of the crops and livestock, so farmers and ranchers depend on groundwater pumped from deep, underground aquifers. Groundwater, like oil, is a limited resource, and in California it’s consumed at an alarming rate.

Image courtesy of Groundwater Foundation

Image courtesy of Groundwater Foundation

Until recently, the extraction of groundwater in California wasn’t regulated in any way. This caused severe environmental degradation, like the drying of nearby domestic drinking water wells, the destruction of infrastructure like roads and canals from land subsidence, the dessication of groundwater-dependent ecosystems, and on the coast, sea water intrusion.

To address these issues, in 2014, California passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, SGMA for short, though some are skeptical that it will be effective.

“It’s great that we have groundwater legislation in California, finally. There’s a lot of good in [SGMA]. But the great tragedy, the absolute great tragedy with SGMA is its incredibly long lead in, the fact that it really doesn’t get implemented for 20 years.”

-Adam Keats, Environmental Attorney at the Center for Food Safety

To understand the consequences of this long lead-in to SGMA, we first need to understand the relationship between groundwater use and drought 3.

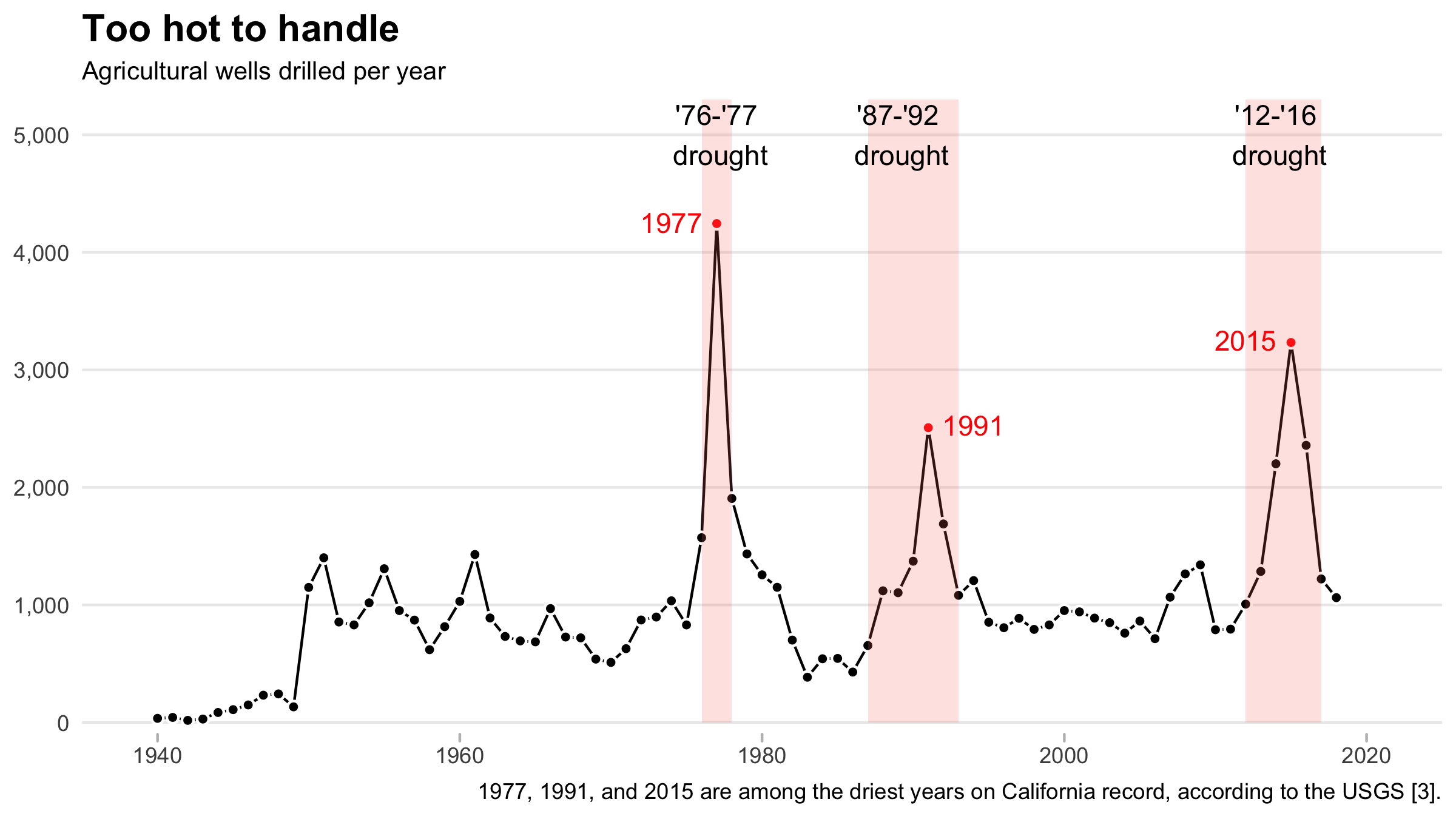

Agricultural well drilling peaks during drought

More agricultural wells are drilled during droughts in California, when surface water is scarce, and demand for groundwater skyrockets.

Whenever a well of any type (e.g. - agricultural, public, domestic, remediation, monitoring) is drilled in California, a well completion report is filed with the state documenting its location, depth, use, and other characteristics 4. These data were mined to observe the number of agricultural wells drilled per year, shown above.

Agricultural wells are far from cheap and can easily cost as much as a house in some areas. The ticket on a 1,000 foot well? $300,000 - $350,000, according to reporting by National Geographic.

Anecdotally, demand for well drillers during the last 2012-2016 drought was so great that some well drillers were booked for months or years out. This creates problems for private domestic well owners, who tend to have shallow wells that are more prone to running dry during drought when nearby pumps are turned on, causing groundwater levels fall. These well owners usually can’t afford to pay for the cost of deepening their wells or drilling new ones, let alone compete with big agriculture for the limited supply of well drillers 5.

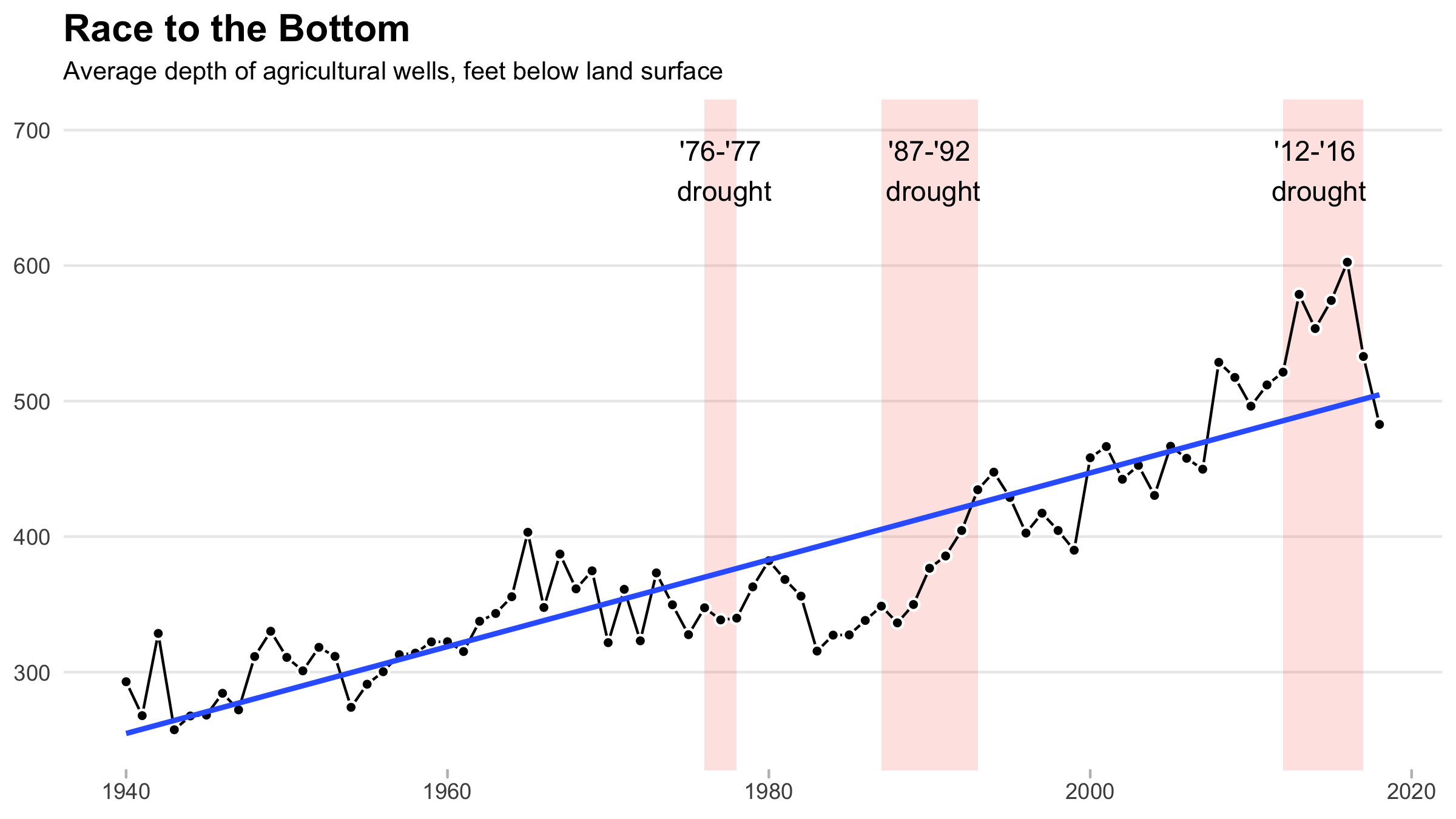

Agricultural wells are being drilled deeper

The average agricultural well today is twice as deep as it was in 1940.

In California’s Central Valley, the hotspot of groundwater extraction, some fear that the 20 year implementation of SGMA creates a regulatory vacuum that some landowners will exploit until apprehended.

Look, in some places [of California] it’s literally a race to the bottom, because there are many farmers that are trying to do things now, before the [the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA)] kicks in.

-Jay Famiglietti, Hydrologist and Executive Director of the Global Institute for Water Security at the University of Saskatchewan

Data from well completion reports in California confirms that agricultural wells are indeed being drilled deeper. Access to deeper groundwater is a hedge against drought, unreliable surface water supply, and the uncertainty of future legislation. It doesn’t hurt to have more access to groundwater before SGMA fully kicks in.

Around the world in 80,000 wells

If you laid each of the roughly 80,000 agricultural wells drilled since 1940 in California on top of one another, they would stretch from Seattle to Guangzhou.

I’m a fan of simple math. If we sum the depth of the roughly 80,000 agricultural wells drilled in California since 1940, we arrive at 33,004,191 feet. That’s 6,251 miles, which is about the distance from Seattle, Washington to my mother’s hometown in Guangzhou, China (6,453 miles). Fun fact, it’s also about 25% of the earth’s circumference (24,901 miles), shown above.

Groundwater depletion in California is part of a larger, worldwide trend

Groundwater extraction in the Middle East, India, Pakistan, China, and Mexico has reached alarming rates, and poses similar sustainability issues to those faced in California today.

The multi-billion dollar agricultural industry fueled by groundwater in California is a bubble of sorts that should be carefully managed. Growth that depends on unsustainable groundwater extraction will eventually come to a head, and cost the region revenue and jobs, in the process displacing tens if not hundreds of thousands of workers and people who depend on local economies created by the agricultural industry.

What is the way forward?

First and foremost, to borrow a tired platitude, we can only manage what we can measure. California, and regions worldwide that seek to curb unsustainable groundwater use need to leverage low-cost, remote sensor networks to monitor groundwater resources in near-real time. New well permits should come conditional with smart meters that measure water extraction and enable the creation of groundwater markets.

Next, with groundwater consumption data in place, policies may be created geared towards the unique conditions, existing water rights, and historical context of the areas of interest.

Ultimately, as shown by the Public Policy Institute of California for the San Joaquin Valley 6, the paths towards groundwater sustainability will depend on the unique water budget of the region, and is likely to include some combination of augmenting supplies, reducing demands by transitioning crops, and in some cases, fallowing fields. Addressing the issue of sustainable groundwater management is complex, requires significant cooperation between a wide array of stakeholders, and will most likely succeed if the solutions proposed are low-cost and benefit multiple parties.

-

CA Agricultural Production Statistics, CA Department of Food and Agriculture, 2018 ↩ ↩2

-

Tim Hearden, “California’s multi-billion-dollar nut boom”, Capital Press, 2016 ↩

-

Rob Gailey and Jay Lund, 2018. “Managing Domestic Well Impacts from Overdraft and Balancing Stakeholder Interests,” California Water Blog ↩

-

Ellen Hanak, Alvar Escriva-Bou, Brian Gray, Sarge Green, Thomas Harter, Jelena Jezdimirovic, Jay Lund, Josué Medellín-Azuara, Peter Moyle, Nathaniel Seav, 2019. “Water and the Future of the San Joaquin Valley,” Public Policy Institute of California. ↩